: Autobiographical story of a disabled boy who managed to overcome the consequences of an incurable disease.

The narration is conducted on behalf of the author and is based on his biography.

Chapters 1–4

Alan was born into a breeder family by the name of Marshall. Father dreamed that his son would become a good rider and win the runners' competition, but his dreams did not come true - in the early nineties, going to school, Alan fell ill with polio, childhood paralysis. In the small Australian village of Turalle, near which the Marshalls lived, they talked about Alan's disease with horror and for some reason connected it with idiocy.

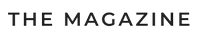

Marshall moved to the Australian state of Victoria from deaf Quisland so that the two oldest daughters could study. He adored horses and believed that they were no different from people. Alan's paternal grandfather, a red-haired English shepherd, came to Australia in the 1940s and in the same year married an Irish woman. Alan's father, the youngest in the family, inherited Irish temperament. Starting at age twelve, Marshall traveled all over Australia, traveling around horses on farms. The parents of Alan's mother were an Irish and a German musician who came to Australia with an orchestra.

Soon after the onset of the disease, Alan's back began to bend, and the tendons in his sore legs were so tightened and hardened that the boy could not straighten his knees. The local doctor, who had a vague idea of polio, advised him to lay Alan on the table three times a day and straighten his legs. This procedure was very painful.

It was not possible to straighten the legs, and parents took Alan to a hospital in a neighboring town. The boy was put in a spacious ward with many beds, where he was the only child.

In his illness, Alan saw only a temporary inconvenience. The pain caused him anger and despair, but, ending, quickly forgotten. People considered Alan's disease a blow of fate and called him a brave boy.

It seemed to me that to call a man brave was like giving him a medal.

He believed that he did not deserve the title of a brave man, and was afraid that sooner or later he would be caught cheating.

A few days later, Alan became akin to the chamber and its inhabitants. His first friend was Angus MacDonald, the manufacturer of the world's best windmills. He once asked Alan why his evening prayer was so long. The boy explained that he has a lot of requests for God, which he adds to ordinary prayer and "omitted this or that request only after it was satisfied."

Alan represented God in the form of a strong man, dressed in a white sheet, was afraid of him, but "nevertheless considered himself a creature, independent of him." At night, the sick moaned and cried out to God. It was strange for Alan to hear this - he believed that adults are so strong that they never experience fear or pain. An exemplary adult for the boy was his father.

Once in the ward they put a man who had drunk to delirium tremens. Alan had never seen such a thing. Drinking, Marshall became cheerful, so the boy was not afraid of the drunk, but the beginner's antics frightened him.

In the morning, Alan presented the unfortunate chicken egg. Breakfast at the hospital was scarce, so many patients bought eggs. In the morning, the nurse collected the signed eggs in a saucepan, and the hospital cook cooked them hard-boiled. Often roommates treated each other. Alan, who was sent a dozen eggs every week, was a particular pleasure.

Soon, the older sister informed Alan that he would undergo surgery.

Chapters 5–9

The operation was performed by Dr. Robertson, a tall man, always dressed in a dandy suit. The boy was lying on the table, waiting for the doctor to put on a white coat, and was thinking about a puddle at the gates of his house.Sister could not jump over her, and Alan always succeeded.

Waking up after the operation, Alan found that he was still lying on the operating table, and his legs were wrapped in wet plaster. The boy was told not to move, but due to tension his leg cramped, this caused a crease on the inside of the cast, and his big toe bent. When the gypsum has dried, the crease began to press on the thigh, and the finger became unbearably painful.

Over the next two weeks, this crease cut into Alan's thigh to the bone. The pain the boy was experiencing was growing stronger.

Even in the brief intervals between bouts of pain, when I was forgotten in a nap, dreams came to me that were full of anguish and suffering.

Alan complained to the doctor, but he decided that the child was mistaken, and his knee did not hurt his finger. A week later, Alan began a local infection, and somewhere on his leg an abscess burst. He told Angus that he could no longer tolerate this pain and seemed to die now. Alarmed Angus called the nurse, and soon the doctor was already sawing plaster on the boy’s leg.

For a week, Alan raced in delirium, and when he came to, Angus was no longer in the ward. The boy’s leg was now in a splint and no longer hurt. Dr. Robertson found that he was too pale and ordered him to be taken to the hospital courtyard in a wheelchair. Alan was not on the street for three months and enjoyed the fresh air.

The nurse left Alan alone. Soon, a familiar boy appeared at the hospital fence - he came with his mother to the hospital and gave Alan different things. Now he wanted to treat his friend with candy and threw the bag over the fence, but he did not reach Alan.

The boy did not doubt for a second that he could not get the candy. He could not drive up to the bag - the wheels of the chair got stuck in the sand. Then Alan began to swing the chair until he knocked it over. The boy was seriously hurt, but still crawled to the sweets.

Alan's act made a big commotion among the carers. They could not understand that the boy did not call for help, because he did not consider himself helpless. Father understood him, but asked to be thrown out of the chair only for the sake of something serious.

After this incident, the doctor brought crutches to Alan. The boy’s right, “bad” leg was completely paralyzed and hung with a whip, but one could lean a little on the “good” left leg. Realizing this, Alan quickly learned to move around on crutches and stopped paying attention to his helpless legs and twisted back.

A few weeks later Alan was discharged.

Chapters 10–12

At first, Alan did not consider himself a cripple, but was soon forced to admit that he fits this definition. Adults sighed over Alan and felt sorry for him, but the children did not pay attention to his mutilation. The “bad” leg, similar to rag, even increased Alan’s authority among his peers - now he had something that others did not have.

The boy was happy, but adults "called this feeling of happiness courage." They forced their children to help Alan and that spoiled everything. The boy began to be treated as a creature different from others. He resisted “this influence from the outside”, did not want to put up with the descent, and gradually from an obedient child turned into a bully.

The child does not suffer from the fact that he is crippled - the suffering falls on the share of those adults who look at him.

After the hospital, the family home with such thin walls that they were swayed by gusts of wind seemed close to Alan, but he quickly got used to it and soon took care of his favorites - parrots, canaries and possum.

Next Saturday, an annual school holiday was to take place - a large picnic by the river, on which runners' competitions were held. Last year, Alan competed, but was too small to win.

This time Alan could not run. His father advised him to watch others run and forget about his sore legs: “When the first runner touches the ribbon with his chest, you will be with him.”

Chapters 13–16

Every morning, the children who lived nearby took Alan to school. They liked it, as they could take turns taking a ride on the boy’s makeshift stroller. There were only two teachers in the school - for junior and senior classes. High school teachers Alan was “afraid like a tiger,” because he punished negligent students with a cane. Not to cry during punishments was considered the highest courage, and Alan “instilled in himself a contempt for the cane”, which aroused the admiration of classmates. The boy did not like to study - in the lessons he turned around, giggled and did not have time to learn the material he had learned.

Gradually, crutches became part of Alan's body. His arms and shoulders "developed out of all proportion." The boy was very tired, often fell and walked all over with bruises and abrasions, but this did not upset him. Alan began to be friends with the strongest boys at school.

I did not understand then that, worshiping any action that embodied strength and dexterity, I kind of compensated for my own inability to take such actions.

Alan felt locked in his own body, like in prison. Before going to bed, he imagined himself to be a dog that rushes through the bush in huge leaps, free from the shackles of a naughty body.

In the summer, an iron tank with drinking water was placed in the school yard. A stampede began near each break near him - everyone wanted to get drunk first. Alan pushed in the crowd along with everyone. Once he had a fight over water with school strongman Steve MacIntyre.

For a week after that they were at enmity and, finally, decided to find out the relationship in a fair fight, which Alan told his parents about. The mother was frightened, but the father knew that sooner or later this would happen, the son must learn to "take punches in the face." Marshall advised his son to fight while sitting and on sticks.

Alan won the battle, after which the teacher punished both “duelists” with a cane.

Chapters 17–19

Alan's best friend was Joe Carmichael, who lived in the neighborhood. His father worked on the estate of Mrs. Carusers, and his mother was a laundress. They were one of the few adults who did not pay attention to Alan's mutilation. Joe also had a younger brother who ran "like a kangaroo rat." Friends considered him to be the most difficult duty.

After school, friends almost never parted. They hunted rabbits in the thicket and looked for bird eggs for their collection. Joe was philosophical about the fall of Alan - he simply sat down and waited for a friend to rest and recover, and never rushed to help if Alan did not ask about it.

Once the boys and two friends went to Mount Tural - an extinct volcano, into the crater of which it was so fun to roll large stones. For Alan, this was a grueling journey, but his friends did not want to wait for him, and the boy had to delay them with cunning in order to climb the mountain and roll the first stone along with everyone.

Once on top, the guys decided to go down to the bottom of the crater, and Alan had to stay. He was annoyed and angry with the Other Boy who lived in him.

He was my double; weak, always complaining, full of fear and apprehension, always begging me to reckon with him, always out of egoism trying to restrain me.

This boy walked on crutches, while Alan perceived himself healthy and strong. Before doing anything, Alan had to free himself from the fears of the Other Boy.

So now Alan did not listen to his second "I", left crutches on the edge of the crater and crawled down on all fours. Going down turned out to be much easier than going upstairs. Alan was having difficulty every yard. Joe tried to help him, but his friends did not wait for them - they quickly went upstairs, threw a huge stone at their friends and fled.

Despite this, Joe and Alan were pleased with the incident.

Chapters 20–22

Marshall, worried that his son was returning from exhausted walks, collected money and bought Alan a real wheelchair, which could be rolled using special levers. The stroller greatly expanded the capabilities of Alan.Now he and Joe often went fishing on the river.

Once, being carried away by catching a huge eel, Joe fell into the water and got wet. The trousers that he hung to dry above the bonfire caught fire. Joe threw them into the water, and they quickly went to the bottom. Returning home in the dark and without pants, the frozen Joe consoled himself by guessing to empty his pockets.

Alan decided to learn how to swim and went to a deep lake on summer evenings. There was no one to help the boy, and he was guided only by pictures in the children's magazine and observations of frogs. A year later, he, the only one from the whole school, swam perfectly.

Near the Marshall's house, tall eucalyptus trees grew, under which tramps and seasonal workers often stopped for the night. Alan's father, who himself traveled all over Australia, called these people travelers and always gave them shelter and food. Alan loved to listen to stories about the places they visited.

I always believed everything that was told to me, and was upset when my father laughed at the stories that I was in a hurry to retell him. It seemed to me that he condemns the people from whom I heard them.

The status of the tramp was determined by the number of belts tied around the duffel bag. One strap was worn by beginners; two are job seekers; three belts were worn temporarily broken; and four - those who did not want to work at all.

These people liked Alan because they never spared him. Crutches seemed to them not such a terrible disaster.

Chapters 23–28

Almost all adults talked with Alan in a protective tone and made fun of his ingenuousness. Only tramps and "seasonal" willingly talked to him. That was Alan’s neighbor, fireman Peter MacLeod, who came home only for the weekend.

Alan really wanted to see how the "virgin thickets" look from where Macleod carries the forest. The neighbor promised to take the boy with him during the holidays, thinking that his parents would not let him go. However, Marshall decided that his son needed to see the world, and Macleod had to take it with him.

I was pleased to recognize that I am alone and free to do as I please. None of the adults now directed me. Everything that I did came from myself.

Leaving the carriage at McLeod's house, Alan went on a journey on long drogues drawn by horses. The first night they spent in an abandoned lumberjack hut, the second on the bank of a stream, and only the next day reached the lumberjack camp.

The four camp residents greeted Alan in surprise. One of them said that the boy would never be able to walk, but MacLeod cut him short: “If the courage of this kid knocks his shoes, they will not wear out.” He did what the boy needed most: raised him to the level of healthy people and aroused respect for him.

Soon, Alan settled into the camp, helped lumberjacks make a fire, cook food, and even visited one of them.

Chapters 29–33

Alan’s enthusiastic story about the trip brought his father great pleasure. Marshall particularly liked that MacLeod allowed the boy to control his horses, which he was very proud of. He finally made sure that a pair of strong and skillful hands means no less than healthy legs.

Marshall believed that his son would never be able to ride, but he was quite capable of learning how to manage a harness. Alan did not agree with this and firmly decided to learn how to sit in the saddle.

A school friend allowed Alan to take his pony to the watering hole. The animal was flexible, and soon the boy learned to stay in the saddle. It took a long time until Alan learned to control the pony, found a way not to fall on sharp turns, dismount and sit in the saddle on his own.

Now I ‹...› searched for places where I couldn’t walk on crutches, and, riding on top of them, I became equal to my comrades.

Two years later, Alan came home on horseback, which greatly surprised and frightened his father.

On the roads of Australia appeared more and more cars.Gradually, cars replaced horses, and Marshall's work became less and less. Alan now rode a pony, which his father traveled to him, and often fell. Marshall taught his son to fall correctly, relaxing all his muscles so that a blow to the ground was softer.

Marshall quickly solved Alan’s difficulties with crutches, but even he did not know what his son would do after school. The shopkeeper from Turalle invited Alan to keep his documentation, but the boy wanted to find a job that required capabilities that were unique to him. He told his father that he wanted to write books. The marshal supported his son, but asked for a little work in the shop to get on his feet.

A few days later, Alan saw in the newspaper an ad for admission to accounting courses at Melbourne College of Commerce. The boy passed the exams and received a full scholarship. Alan's parents decided to move to Melbourne so as not to leave their son alone.

Joe said that it would probably be difficult for a friend to walk around the huge city on crutches. “Who thinks of crutches!” Alan exclaimed with contempt.