The poem begins with a description of the Moscow ball. The guests gathered, elderly ladies in magnificent dresses sit near the walls and look at the crowd with "dumb attention". Nobles in ribbons and stars sit at the cards and sometimes come to look at the dancers. Young beauties are spinning, "The hussar twists his mustache, / The writer stiffly quips." Suddenly everyone was embarrassed; rained questions. Princess Nina suddenly left the ball. “In a quadrille, twirling merrily, / Suddenly she died! - What is the reason? / Ah, my goodness! Tell me, prince, / Tell me what is with Princess Nina, / your wife? ” “God knows,” the prince answers with marital indifference, busy with his Boston. The poet answers instead of the prince. The answer is a poem.

There is a lot of talk about the black-eyed beauty Princess Nina, and not without reason: until recently, her house was filled with red tape and pretty young men, seductive ties replaced one another; Nina, it seems, is not capable of true love: “In her is the heat of a drunken Bacchante, / Hot fever is not the heat of love.” In her lovers, she sees not themselves, but the “wayward face” created in her dreams; the charm passes and she leaves them cold and without regret.

But recently, Nina’s life has changed: “the messenger of fate appeared to her.”

Arseny recently returned from foreign lands. There is no pampered beauty of ordinary visitors to Nina's house; there are traces of hard experience on his face, in his eyes “carelessness is gloomy”, not a smile, but a smile on his lips. In conversations, Arseny discovers the knowledge of people, his jokes are crafty and sharp, he makes judicious judgments about art; he is restrained and outwardly cold, but it is clear that he is capable of experiencing strong feelings.

Experienced enough, Arseny does not immediately succumb to Nina’s charm, although she uses all the means she knows to attract him; finally the “omnipotent moment” brings them together. Nina is “full of the bliss of a new life”; but after two to three days Arseny was again as before: stern, dull and distracted. All attempts by Nina to amuse him are futile.

Finally, she demands an explanation: “Tell me, what is your contempt for?” Nina is afraid that Arsenia repels the thought of her turbulent past; the memories are hard for herself. She asks Arseny to run away with her - at least to Italy, which he loves so much - and there, in obscurity and tranquility, spend the rest of her life. Arseny is silent, and Nina cannot but notice the “stubborn cold” of his soul; the desperate Nina cries and calls her unhappy love the execution from above for sins. Here, with assurances of love, Arseny temporarily reassures Nina.

The next evening, lovers sit peacefully in Nina's house; Nina is dozing, Arseny in thoughtfulness draws something carelessly on a business card and suddenly inadvertently exclaims: “How similar!” Nina is sure that Arseny painted her portrait; looks - and sees a woman who is not at all like her: “a cutesy girl / With sweet stupidity in her eyes, / In hairy curls like a lap-dog / With a sleepy smile on her lips!” First, Nina proudly declares that she does not believe that such a rival could be for her; but jealousy torments her: her face is deathly pale and covered with cold sweat, she breathes a little, her lips turn blue, and for a "long moment" she almost becomes speechless. Finally, Nina begs Arseny to tell her everything, admits that jealousy kills her, and says, by the way, that she has a ring with poison - the talisman of the East.

Arseny takes Nina by the hand and tells that he had a bride Olga, blue-eyed and curly; he grew up with her. After the engagement, Arseny introduced his friend into Olga’s house and soon became jealous of him; Arsenia Olga replies to reproaches with “childish laughter”; furious Arseny leaves her, starts a quarrel with an opponent, they shoot, Arseny is seriously injured. Having recovered, Arseniy goes abroad. For the first time, he said, he could only console himself with Nina.

Arseny Nina does not respond to confession; it’s only visible that she is exhausted.

A few more weeks passed in quarrels and "unhappy" reconciliations. Once - Arseny had not been with Nina for several days - Nina was brought a letter, in which Arseny said goodbye to her: he met Olga and realized that his jealousy was "wrong and ridiculous."

Nina doesn’t leave and doesn’t accept anyone, refuses food and is “motionless, dumb, / Sits also from the place of one / Does not take her eyes off”. Suddenly her husband comes to her: embarrassed by the strange behavior of Nina, he reproaches her for “quirks” and calls to the ball, where, incidentally, should be young - Arseny and Olga. “Strange animated,” Nina agrees, takes on long-forgotten outfits and, seeing how she has become ill, decides to make up for the first time to prevent the young rival from triumphing over her. However, she did not have the strength to withstand the ball: she felt sick, and she was leaving home.

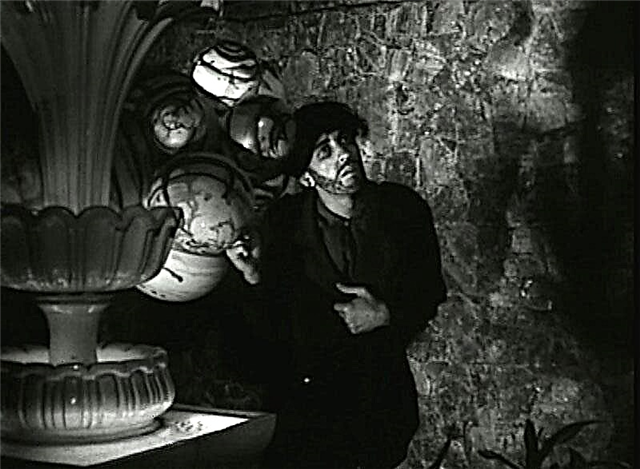

Deep night. In Nina’s bedroom, the lamp in front of the icon burns weakly. “Around, a deep, dead dream!” The princess sits "motionless" in a ball gown. An old nanny of Nina appears, corrects the lamp, “and the light is unexpected and alive / Suddenly illuminates all peace”. After praying, the nanny is about to leave, suddenly notices Nina and begins to feel sorry and reproach her: “And what is wrong with your fate? <...> You forgot God ... "Kissing Nina's hand goodbye, the nanny feels that she is" icy-cold, "looking into her face, she sees:" A move hasty to her death: / Her eyes are standing and her mouth is in foam .. . ”Nina fulfilled the promise given to Arseny and was poisoned.

The poem ends with a satirical description of the magnificent funeral: one carriage comes after another to the prince's house; the important silence of the crowd gives way to a noisy voice, and the widower himself is soon already occupied with a "hot theological prehn" with some kind of hypocrite. Nina is buried peacefully, like a Christian: the light did not know about her suicide. The poet, who had lunch with her on Thursdays, devoid of lunch, honored her memory with rhymes; they were published in the Ladies' Journal.