In November 1932, he was the senior owner of a furniture company, the owner of a solid current bank account and a beautiful mansion in Berlin, built and furnished to his own liking. The work carries him a little, he appreciates his worthy, substantial leisure more. A passionate bibliophile, Gustav writes about people and books of the 18th century. He is very glad of the opportunity to conclude an agreement with the publishing house on Lessing's biography. He is healthy, complacent, full of energy, lives with taste and pleasure.

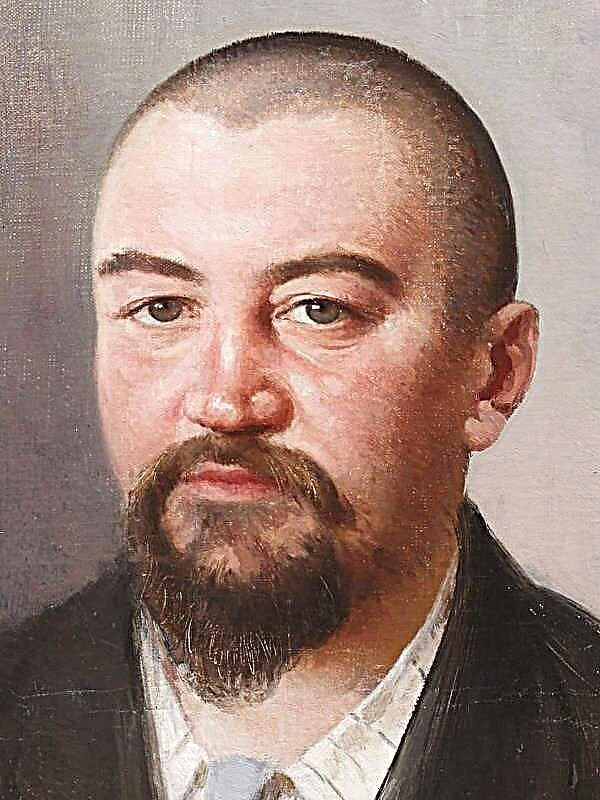

On his birthday, Gustav gathers family, close friends, good friends. Brother Martin presents him with a family heirloom - a portrait of their grandfather, the founder of the company, Emanuel Opperman, who had previously decorated the office in the main office of the Trading House. Sibyll Rauch arrives with congratulations, their romance has been going on for ten years, but Gustav prefers not to impose chains of legality on this connection. Sibylla is twenty years younger than him, under his influence, she began to write and now earns literary work. Newspapers readily print her lyrical sketches and short stories. And yet for Gustav, in spite of a long affection and tender relationship, Sibylla always remains on the periphery of his existence. There is a deeper feeling in his soul for Anna, two years of acquaintance with which are full of quarrels and anxieties. Anna is energetic and active, she has an independent disposition and a strong character. She lives in Stuttgart, works as a secretary in the board of power plants. Their meetings are now rare, however, as are the letters they exchange. The guests of Gustav, people with prosperity and status, who settled down well in life, are absorbed in their own, rather narrow interests and attach little importance to what is happening in the country. Fascism seems to them only a crude demagogy, encouraged by the militarists and feudal lords who speculate on the dark instincts of the petty bourgeois.

However, reality now and then roughly breaks into their rather closed world. Martin, who actually runs the business of the company, is concerned about relations with long-time rival Heinrich Wels, who now heads the district department of the National Socialist Party. If the Oppermans produce standard factory-made furniture with low prices, then in Wels workshops products are made by hand, artisanal and lose due to their high cost. The successes of the Oppermans are much more striking in Wels' ambition than in his thirst for profit. More than once he talked about the possible merger of both companies, or at least closer cooperation, and instinct tells Martin that in the current situation of crisis and growing anti-Semitism, this would be a life-saving option, but he still pulls with a decision, considering that there is no need to go to this agreement yet. In the end, it is possible to turn the Jewish company Oppermans into a joint-stock company with the neutral, not suspicious name of “German furniture”.

Jacques Lavendel, husband of the younger sister of the Oppermans Clara, regrets that Martin missed a chance, failed to negotiate with Wels. Martin is annoyed by his manner of calling unpleasant things by their proper names, but we must pay tribute, brother-in-law is a wonderful businessman, a man with a great fortune, cunning and resourceful. You can, of course, transfer the Oppermans furniture company to his Name, because he had sensibly gained American citizenship for himself.

Another brother of Gustav - the doctor Edgar Opperman - heads the city clinic, until self-forgetfulness, he loves everything related to his profession as a surgeon and hates administration. Newspapers attack him, he allegedly uses the poor, free patients for his dangerous experiments, but the professor is trying in every possible way to protect himself from the vile reality. “I am a German doctor, a German scientist, there is no German medicine or Jewish medicine, there is science, and nothing more!” - he repeats to the Privy Advisor to Lorenz, the chief physician of all city clinics.

Christmas is coming. Professor Arthur Mülheim, legal adviser to the company, offers Gustav to transfer his money abroad. He responds with a refusal: he loves Germany and considers dishonorable to withdraw his capital from it. Gustav is sure that the vast majority of Germans on the side of truth and reason, no matter how the Nazis pour money and promises, they will not be able to fool a third of the population. What does the Führer end up with, he discusses in a friendly circle, a shame in a yarmana booth or an insurance agent?

The seizure of power by the fascists overwhelms the Oppermans with their imaginary surprise. In their opinion, Hitler - a parrot, helplessly babbling at someone else's prompting, is wholly in the hands of big capital. The German people will figure out loud demagoguery, will not fall into a state of barbarism, Gustav believes. He disapproves of the feverish activities of relatives to create a joint-stock company, considering their arguments the arguments of “confused businessmen with their eternal penniless skepticism”. He himself is very flattered by the proposal to sign an appeal against the growing barbarism and savagery of public life. Mulheim regards this step as unacceptable naivety, which will cost dearly.

The seventeen-year-old son of Martin Bertold has a conflict with the new teacher Vogelsang. Until now, the director of the gymnasium, Francois, a friend of Gustav, has managed to protect his school from politics, but the ardent Nazi who has appeared within its walls is gradually setting his own order here, and the soft, intelligent director can only watch with caution as nationalism quickly envelops the head with a wide front fog his pupils. The cause of the conflict is a report prepared by Bertold on Arminius Hermanets. How can one criticize, debunk one of the greatest feats of the people, Vogelsang is indignant, regarding this as an anti-German, anti-patriotic act. Francois does not dare to defend a smart young man against a frenzied fool, his teacher. Berthold does not find understanding with his relatives. They believe that the whole story is not worth a damn, and they advise to bring the required apology. Not wanting to sacrifice principles, Berthold takes a large amount of sleeping pills and dies.

A wave of racist persecution is expanding, but they still do not dare to hurt Professor Edgar Opperman in the medical world, because he is world famous. And yet he repeats to Lorentz that he will drop everything himself, without waiting until they throw him away. The country is sick, says his privy adviser, but this is not an acute, but a chronic disease.

Martin, having broken himself, is forced to accept the outrageous terms of the agreement with Wels, but still he manages to achieve a certain business success, for which it was so dearly paid.

After setting fire to the Reichstag, Mülheim insisted that Gustav immediately go abroad. For his friend the novelist Friedrich-Wilhelm Gutvetter, this causes confusion: how can you not be present at a stunningly interesting sight - the sudden capture of a civilized country by barbarians.

Gustav lives in Switzerland. He seeks to communicate with compatriots, wanting to better understand what is happening in Germany, terrible reports are published in newspapers here. From Klaus Frischlin, who headed the art department of the company, he learns that his Berlin mansion was confiscated by the Nazis, some of his friends are in concentration camps. Gutvetter gained fame as the “great truly German poet,” the Nazis recognized him as theirs. In his grandiloquent syllable, he describes the image of the “New Man,” asserting his original wild instincts. Arriving at Gustav to spend her vacation, Anna is holding on as if nothing special were happening in Germany. According to the manufacturer Weinberg, you can get along with the Nazis, the coup affected the country's economy not bad. Lawyer Bilfinger gives Gustav documents for review, from which he learns about monstrous terror, under the new regime, lies are confessed as the highest political principle, tortures and killings occur, lawlessness reigns.

At Lavendel’s house on the shores of Lake Lugano, the entire Opperman family celebrates Passover. We can assume they were lucky. Only a few managed to escape, the others simply were not released, and if someone was given the opportunity to leave, they seized their property. Martin, who happened to get acquainted with the Nazi dungeons, is going to open a store in London, Edgar is going to organize his own laboratory in Paris. His daughter Ruth and beloved assistant Jacobi left for Tel Aviv. Lavendel intends to go on a trip, to visit America, Russia, Palestine and see firsthand what is being done and where. He is in the most advantageous position - he has his own home here, he has citizenship, and now they don’t have their own shelter, when their passports expire, they are unlikely to renew them. Fascism is hated by the Oppermans, not only because they knocked out the ground under their feet, outlawed them, but also because it violated the "system of things", and shifted all ideas about good and evil, morality and duty.

Gustav does not want to stay away, he unsuccessfully tries to find contacts with the underground, and then returns to his homeland under a foreign passport, intending to tell the Germans about the abominations taking place in the country, try to open their eyes, arouse their sleepy feelings. Soon he is being arrested. In the concentration camp, he is exhausted by the overwhelming work of laying a highway, tormented by frustration: he was a fool that returned. No one benefits from this.

Upon learning of the incident, Mulheim and Lavendel take all measures for his release. When Sibylla arrives at the camp, she finds an exhausted, thin, dirty old man there. Gustav is transported across the border to the Czech Republic, placed in a sanatorium, where he dies in two months. Reporting this in a letter to Gustav's nephew Heinrich Lavendell, Frischlin expresses admiration for the act of his uncle, who, neglecting danger, showed his willingness to stand up for a just and useful cause.